Sometimes, when I’m walking down the street in Chinatown, surrounded by fake Fendis and Vuittons and Pradas, I ask myself, “Will anyone know this is fake?”

Sometimes, when I’m walking down the street in Chinatown, surrounded by fake Fendis and Vuittons and Pradas, I ask myself, “Will anyone know this is fake?”

It seems that this thought process is not limited to fashionable Manhattan women hoping to save a thousand dollars on their next handbag, but extends to English men, hoping to save time making fondue.

While I was visiting Mr. English in London last week, he told me that his father, who will hereafter be referred to as Sir English, had just returned from Normandy bearing loads of cheese, and had invited us over that night for fondue.

While I was visiting Mr. English in London last week, he told me that his father, who will hereafter be referred to as Sir English, had just returned from Normandy bearing loads of cheese, and had invited us over that night for fondue.

“Fondue!?”

“Yes, fondue.”

We were coincidentally standing among all the real Fendis and Vuittons and Pradas in Harrods, and I immediately dropped the Valentino I had been inspecting, grabbed his hand, and tugged him into the food halls.

“What can I bring to Sir English’s house?” I chanted to myself. I am always frightfully on edge about appearing as the uncouth ugly American to Mr. English’s family and friends. “What about Laduree macarons?” (They have an outpost there). Veto. Then, knowing Sir English, I thought, “Let’s get some really good beer like they have in Normandy.” Where’s the beer in Harrods? Then it hit me: “I’m buying the beigneuses! Tell your father all he needs is cheese!”

The food halls at Harrods, if you like food, are similar to how you may envision heaven, should you be a religious person. Whether or not you are, witnessing room after room of turkey to Turkish delight tumbling from gilded baroque cases may at least convince you that there is a God. I always think of shopping there as the modern day equivalent to the kings of Britain hunting white stags and unicorn in old tapestries—except, now I’m the royalty and I can just ask the man behind the counter for a piece of venison instead of shooting it in the heart with the claws of my falcon.

It was within this wonderland that I found my beigneuses, a French word meaning “bathers,” so called because fondue is known in the produce community as the Turkish baths for bread and vegetables. I bought Spanish chorizo and Rosette de Lyons, a French salami. I bought endive and Pink lady apples. I bought boule and baguette. I bought too much.

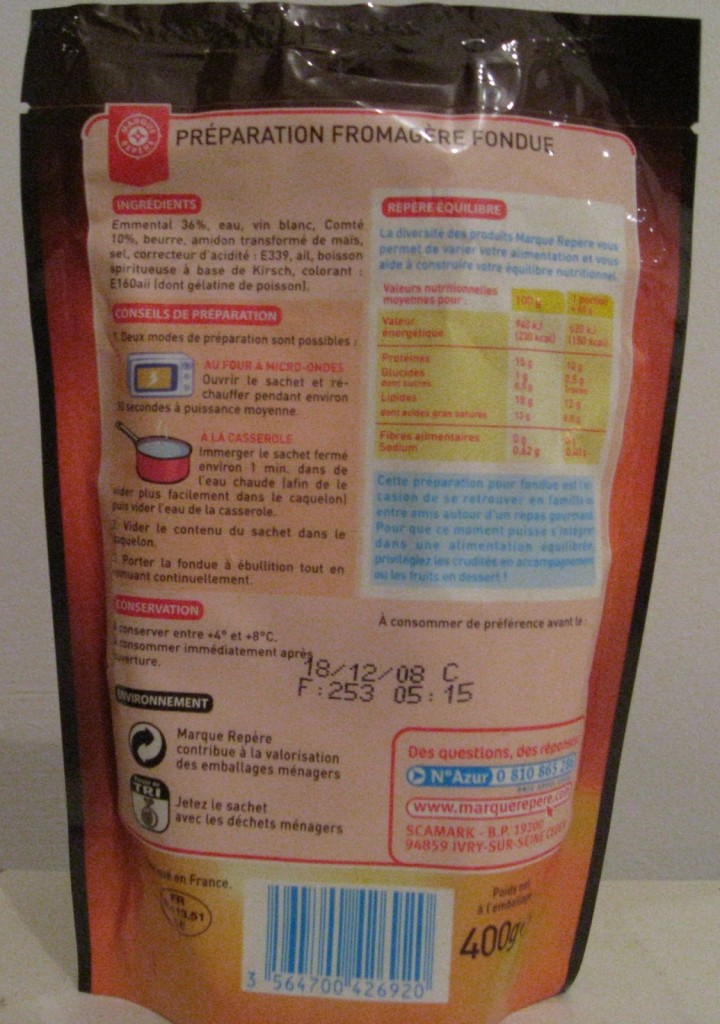

Because he is a bit of a gourmet, Sir English knew to leave the fondue preparation until the last minute. But he wasn’t counting on my making myself at home in his kitchen, chopping up endive spears and baguette crusts. He walked over to the refrigerator and said, “Kerry, I hoped you spare you the sight of this,” and pulled out a plastic pouch that said FONDUE.

Some foodies might have been miffed, but I was fascinated. I have a secret obsession with French packaged foods, because they always leave one thought in my mind: why don’t we have this in America? How can Publix stock all of its thousands of square yards of shelves, and not find room for plastic-packaged fondue?

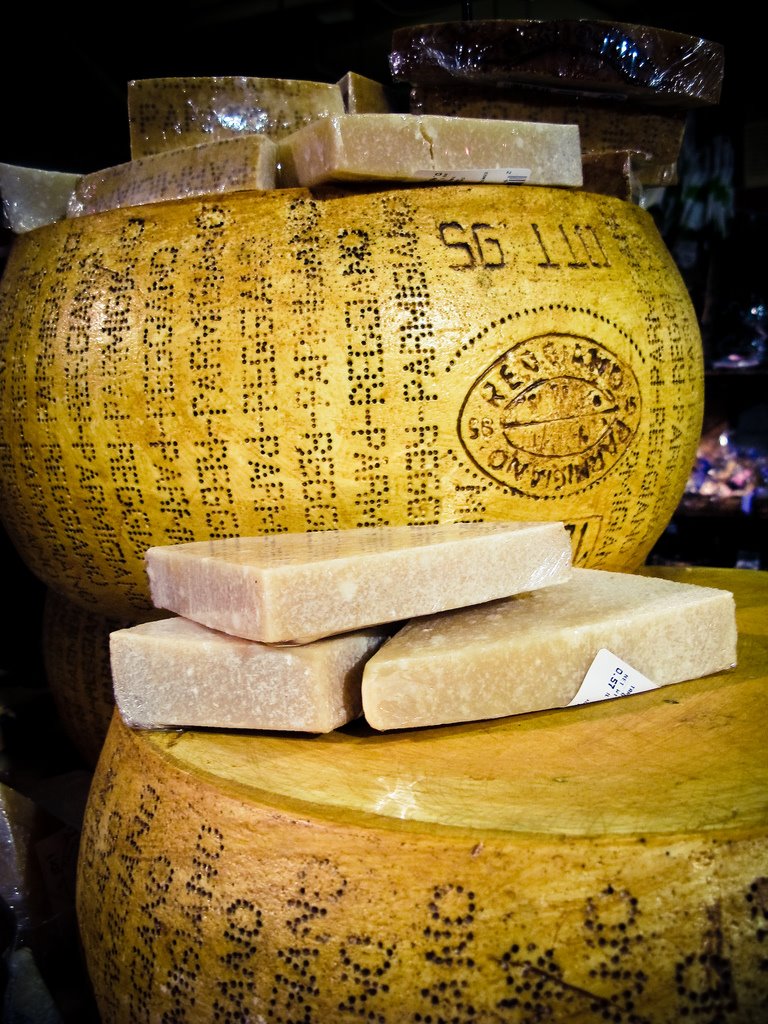

The pouch contained the three primary Swiss fondue cheeses: Emmenthaler, Gruyere, and Comte. It had white wine and Kirsch. Butter and garlic. Meekfully anticipating reproach, Sir English pulled out a few wedges of emmenthaler from the fridge, but I turned to him and yelped, “This is amazing.”

The pouch contained the three primary Swiss fondue cheeses: Emmenthaler, Gruyere, and Comte. It had white wine and Kirsch. Butter and garlic. Meekfully anticipating reproach, Sir English pulled out a few wedges of emmenthaler from the fridge, but I turned to him and yelped, “This is amazing.”

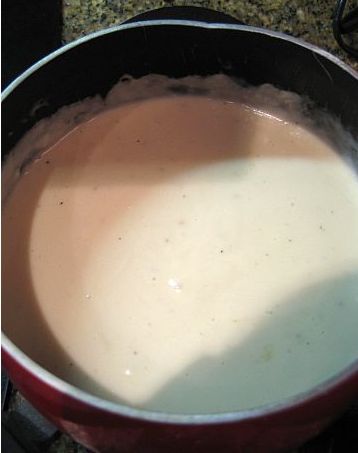

I then taught him how make Fondue Savoyarde, which is the traditional fondue most of us think of when we daydream about fondue. He rubbed the fondue pot with a cut clove of garlic, and added some white wine and fresh thyme. Then, we stirred in the packet of fondue, and grated in a bunch of fresh Emmenthaler. We used the pouched fondue as a flavorful binder, instead of cornstarch, to prevent the fondue from separating. And so Sir English and I brought to the table a pot of liquid gold.

So, to answer the existential question of the post, no. No one can tell it’s a fake. Or rather, perhaps an editor at Vogue could tell it’s a fake Fendi, or a cheese monger in Savoy could taste the plastic-wrapped cheese, but for all intents and purposes, our semi-packaged fondue brought extreme gastronomic pleasure into Sir English’s house. Mr. English’s sister, Miss English, abandoned her cheese-free diet to jostle endive spears with me in the pot. Mr. English found that bread was a much more efficient and desirable way to clean a fondue pot than a sponge and soap. Sir English poured another round of Pommeau, a Norman apple brandy, as we all crowded close to the flame, and all were warmed, inside and out.

So, to answer the existential question of the post, no. No one can tell it’s a fake. Or rather, perhaps an editor at Vogue could tell it’s a fake Fendi, or a cheese monger in Savoy could taste the plastic-wrapped cheese, but for all intents and purposes, our semi-packaged fondue brought extreme gastronomic pleasure into Sir English’s house. Mr. English’s sister, Miss English, abandoned her cheese-free diet to jostle endive spears with me in the pot. Mr. English found that bread was a much more efficient and desirable way to clean a fondue pot than a sponge and soap. Sir English poured another round of Pommeau, a Norman apple brandy, as we all crowded close to the flame, and all were warmed, inside and out.

It all proves that the answers to most of life’s more difficult questions can be found in a French supermarket—or in a French woman’s closet (existentialism is French, after all, mes amis). If you mix high and low, and accessorize well, no one will suspect a thing.

Good advice for braving the recession ahead.